Since Fidel Castro’s ascent to power in 1959, U.S.-Cuba ties have endured a nuclear crisis, a long U.S. economic embargo, and persistent political hostilities. The diplomatic relationship thawed under President Barack Obama, but many restrictions have since been renewed.

Fidel Castro establishes a revolutionary socialist state in Cuba after he and a group of guerrilla fighters successfully revolt against President Fulgencio Batista. Batista, who had been supported by the U.S. government for his anticommunist stance, flees the country after seven years of dictatorial rule. Castro gradually strengthens relations with the Soviet Union.

Castro nationalizes all foreign assets in Cuba, hikes taxes on U.S. imports, and establishes trade deals with the Soviet Union. President Dwight D. Eisenhower retaliates by slashing the import quota for Cuban sugar, freezing Cuban assets in the United States, imposing a near-full trade embargo, and cutting off diplomatic ties with the Castro government.

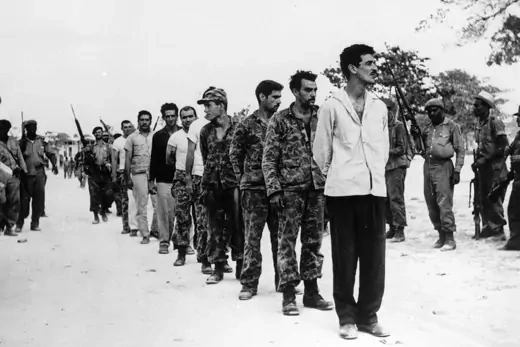

April 17, 1961

Executing a plan developed and approved by the Eisenhower administration, President John F. Kennedy deploys a brigade of 1,400 CIA-sponsored Cuban exiles to overthrow Fidel Castro. The Cuban military defeats the force within three days, after several mishaps disadvantage the invaders and reveal U.S. involvement. Despite the failed invasion, U.S. administrations over the next several decades conduct covert operations against Cuba.

February 7, 1962

The Kennedy administration imposes an embargo on Cuba that prohibits all trade. Cuba, whose economy greatly depended on trade with the United States, loses approximately $130 billion over the next nearly sixty years, according to Cuban government and United Nations estimates.

October 14 – 28, 1962

U.S. spy satellites discover that Cuba has allowed the Soviet Union to build nuclear missile bases on the island. In response, Kennedy demands the Soviet weapons be removed and orders a naval quarantine of Cuba, igniting a thirteen-day standoff. With the threat of nuclear war on the horizon, the United States negotiates with the USSR via back channels. As the crisis nears its third week, Kennedy secretly agrees to withdraw U.S. nuclear missiles from Turkey within a few months if the Soviet Union withdraws its missiles from Cuba. Kennedy also pledges not to invade Cuba. Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev accepts the deal and announces that he will order the missiles removed. The following July, Kennedy prohibits U.S. nationals from traveling to Cuba.

Castro indicates in a September 1965 speech that Cubans can leave for the United States of their own free will, saying that “nobody who wants to go need go by stealth.” Days later, President Lyndon B. Johnson announces he will open U.S. borders to all Cubans and signs into law an immigration bill that gives preference to Cuban migrants with family ties to U.S. citizens or residents. The U.S. State Department estimates that some 270,000 Cubans have arrived in the United States since Castro took power. In November 1966, Johnson enacts a law that allows Cubans who reach the United States to pursue permanent residency after one year.

September 1977

President Jimmy Carter reaches an agreement with Castro to resume a limited diplomatic exchange, allowing officials from the two countries to communicate regularly. The United States opens an interests section with a small staff in its former embassy in Havana under the auspices of the Swiss embassy. Switzerland had taken over U.S. interests in Cuba in 1961. Meanwhile, Cuba opens an interests section in Washington, DC, under the auspices of the embassy of Czechoslovakia.

April 1980 – October 1980

Cuba faces intense pressure from thousands of Cubans hoping to flee the country as its economy suffers from a spike in oil prices and the continued U.S. embargo. Following a forty-eight-hour debacle in which ten thousand Cubans crowded at the gates of the Peruvian embassy to gain asylum, Castro states that anyone wishing to leave Cuba for Florida may do so from Mariel Harbor over the next six months. President Carter welcomes Cubans to the United States “with open arms,” and as many as 125,000 Cubans take part in the boatlift.

March 1982President Ronald Reagan designates Cuba a state sponsor of terrorism, censuring the Castro government for providing support to militant communist groups in African and Latin American countries including Angola, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Nicaragua. Cuba maintains that “acts by legitimate national liberation movements cannot be defined as terrorism,” according to a U.S. State Department report. Due to the heavy economic sanctions already in place, the designation is largely a symbolic act.

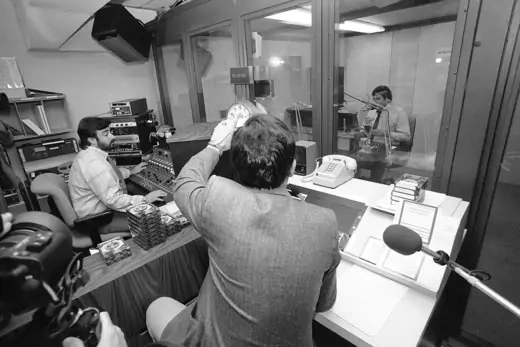

May 20, 1985

Radio Martí begins broadcasting news and entertainment programming to Cuba from studios in the United States. The federally funded station was proposed by Reagan in 1981 and created by Congress two years later. The Cuban government condemns the service as U.S. propaganda, jams the new station’s broadcasts, and calls its use of independence hero José Martí’s name a “gross insult.” Castro suspends an immigration agreement that would have allowed up to twenty thousand Cubans a year to immigrate to the United States and provided for the repatriation of some three thousand Cubans with criminal records or who suffer from mental illness. Cuba also halts visits by Cubans living in the United States.

October 23, 1992President George H.W. Bush signs the Cuban Democracy Act, which increases U.S. economic sanctions on Cuba. The move follows the Soviet Union’s 1991 collapse, with Bush stating that Cuba’s “special relationship with the former Soviet Union has all but ended. And we’ve worked to ensure that no other government helps this, the cruelest of regimes.” The statute bars vessels that have exchanged goods with Cuba in the previous 180 days from docking at U.S. ports and prohibits foreign subsidiaries of U.S. businesses from trading with Cuba. The legislation also limits the amount of U.S. currency traded with Cuba. The act does, however, offer a path to normalizing relations that is conditioned on Castro’s government making significant economic and political reforms.

1994 – 1995

Havana and Washington implement two accords aimed at addressing the thousands of Cubans attempting to enter the United States annually. The first follows an abrupt policy change by President Bill Clinton in August 1994 that calls for all Cubans rescued at sea to be brought to the U.S. naval base at Guantánamo Bay. It outlines terms for future legal immigration from Cuba to the United States, setting the number of Cubans allowed to enter the U.S. annually at a minimum of twenty thousand (not including immediate relatives of U.S. citizens). The second accord establishes the “wet foot, dry foot” policy [PDF], in which Cubans intercepted by U.S. authorities at sea are sent home while those who make landfall in the United States are allowed to remain and pursue permanent residency after one year. The agreement also allows for more than thirty thousand Cubans detained at Guantánamo Bay to enter the United States on parole status.