John Stanton ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

City, University of London apporte des fonds en tant que membre fondateur de The Conversation UK.

Voir les partenaires de The Conversation France

Around 20 miles from central London, where modern-day government and democracy shape the lives of citizens throughout the United Kingdom, the Thames meanders peacefully through nondescript English countryside. This is just another part of the green and pleasant land that has come to define much of these shores.

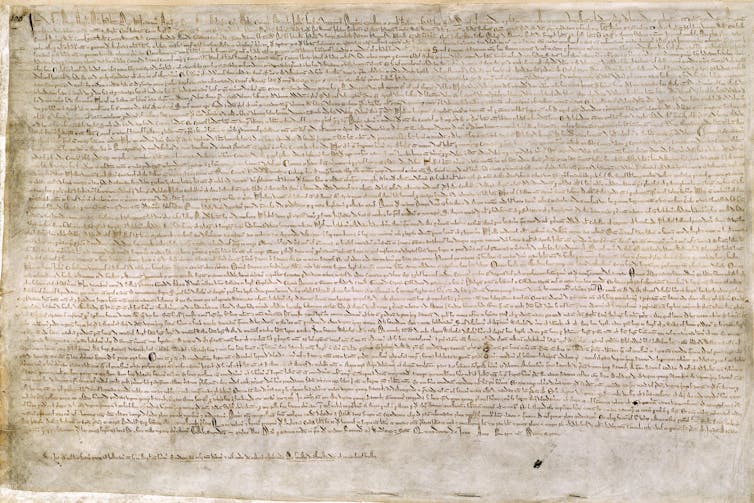

Except that there’s something rather different about this rural corner of England. These riverside fields at Runnymede are reputed to be the setting for one of the most significant moments in UK democratic and constitutional history. The National Trust labels it “the birthplace of modern democracy”, while an impressive monument commemorates a “symbol of freedom under law”. It was here, of course, that the Magna Carta is said to have been sealed on June 15 1215 under the title of the “Great Charter”.

The catalyst for Magna Carta was the tyrannical rule of King John and, in particular, his imposition of arbitrary taxes upon the barons. The sealing of Magna Carta marked the first time that the notion that an unelected sovereign should be restrained under law was officially recognised. From then on, the idea that citizens should not be subjected to the arbitrary rule of a tyrannical monarch but instead be ruled and governed upon foundations of accepted legal process and law had a legal foundation.

This was, in essence, an evolution of the Aristotlean idea of the supremacy of law in preference to the supremacy of man. Such a concept is today known as the rule of law and Magna Carta is widely accepted as being the birth of such rule in the UK constitution. So, a big moment.

Of course, understandings of the rule of law have altered and developed from that determined by King John’s subjection. Theorists and academics have, over the centuries, debated and set out contrasting views as to what Magna Carta means in practice.

Adherence to the rule of law is now believed to demand more than due legal process in preference to arbitrary rule. It now (for example) demands the equal subjection of all people – whatever their rank or position – to the ordinary law of the land; the appreciation and protection of individual rights and liberties and the ultimate ability of all citizens to be able to conduct themselves freely in a system guided by law and legal principle.

To say that the modern UK constitution is one that adheres to the basic principles of the rule of law is to state the obvious.

That said, the UK constitutional system is markedly different from that which prevailed in the early 13th century. Monarchical legal power is virtually, if not completely, non-existent. Legislative and executive functions are in a sense fused through an institution built upon democracy and universal adult suffrage. The needs of citizens are fundamentally more diverse and complex than they were 800 years ago.

Consequently, the system involves a great deal more discretionary authority than traditional rule of law theorists might find acceptable. As well as this, competing interests and concerns of the state often demand difficult balances and compromises to be struck between pressing political matters and concerns on the one hand, and individual liberties and core values of due process on the other. Even these occurrences are carefully regulated and debated as part of a constitutional system that, while highly peculiar, is adaptable and flexible to the constantly shifting needs and concerns of society.

The core values set out by the Magna Carta, therefore – due legal process over arbitrary power and the freedom to act within a system guided by legal principle – are still very much at the heart of our constitution, even if that system has evolved and changed beyond all recognition.

Over the centuries most of the Great Charter’s clauses have been repealed. Only three of the original 63 clauses remain in force: those providing for the freedom of the Church of England; the protection of the liberties and free customs of the City of London; and the protection of individuals from imprisonment or punishment without due process.

But the legacy of Magna Carta runs much deeper. The establishment of the rule of law at Runnymede 800 years ago went on to inspire and shape the development of the UK constitution and, indeed, the constitutions of democratic systems the world over.